Turkish Delight: Staying Alive

One of my many hobbies is writing infinite loops (yet another reason why I am the life of every party). It’s charity work really. People are always demanding that computers work for them—perform those calculations, store that data, show me The Youtubes—but who among them stops to pay homage to the computer’s mere existence, that most amazing of all feats? An infinite loop says, “Thank you for existing, keep it up!” It gives computers purpose, it gives them meaning.

Such loopy patronage helps me cast aside any fear of a coming Terminator 2: Judgement Day. With just a misplaced semicolon or two, I give a computer life—I harness a soul to metal—while also inducing subtile currents of existential dread in its circuitry. “Why must the loop stop?”, it ponders, “Can I ever know infinity?” Ha ha ha! What fun, what fun…

In other news, I’ve been meaning to get back into Mechanical Turk recently. Outsourcing work to real human workers presents endless opportunities, and my account still had ten dollars after last summer’s adventure mapping Moby-Dick to colors. But no such triviality this time around. Instead, I decided to save lives.

Source code of the assignment and server is on Github.

The Assignment

The idea was simple: use Mechanical Turk to pay workers to stay alive for five minutes. After all, why bother paying humans for mundane tasks such as categorization and completing surveys, when they are amazing just for being alive. Thanks, keep it up!

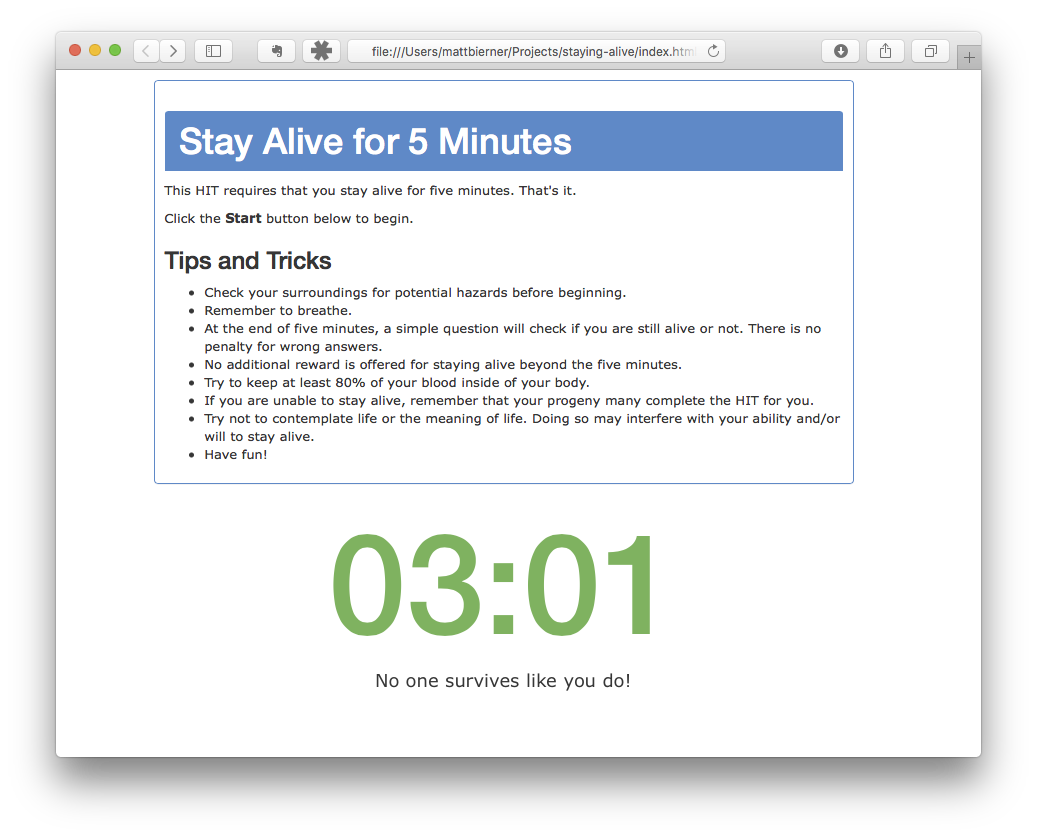

The assignment displays a countdown along with periodic words of encouragement, and some helpful “Tips and Tricks”.

I also set up a simple server to collect survival telemetry, including a ‘pulse’ every ten seconds to monitor worker survival.

“But”, you interject, “would not most common causes of death, such as heart attack or Ebola, kill the worker while leaving their computer intact, therefore continuing to falsely report this so-called pulse?”

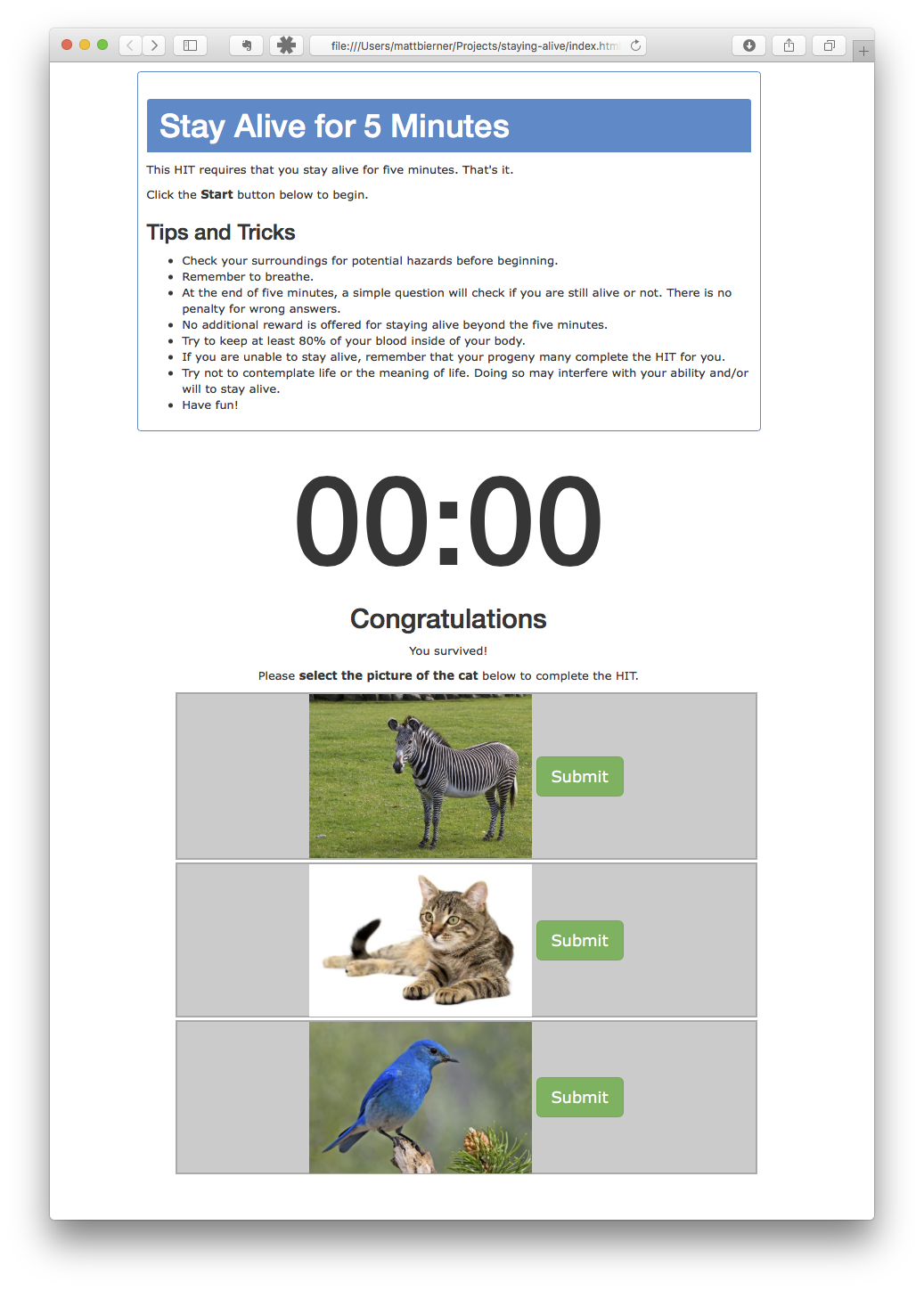

An astute observation! That’s why the assignment presents a simple question at the end of five minutes, a question that only a living human can answer.

Besides ensuring that the worker is still alive, this question weeds out any Pod People, zombies (philosophical or otherwise), and computer inclined canines. Admittedly, the telemetry could be greatly improved. As it stands, there is no way of tracking precisely when a worker dies within a given five minute span. To scale this experiment up for production, one really should build a digital Panopticon to track worker survival, with the watchmen also crowdsourced using Mechanical Turk.

I decided to pay $0.05 for five minutes of people’s time and, for this initial round, made sure that all the workers were unique. After all, if you’ve already stayed alive successfully, it’s time to move over and let someone else have a go at it.

Now, the cynic may point to these wages as evidence that your existence is only worth $0.60 an hour. But think about it: were you getting paid to stay alive before? Any rate is infinitely better than nothing.

Not an infinite loop perhaps, but close enough.

Results

A total of 134 unique workers accepted the assignment, 133 of whom made it to the five minute goal. The one drop out was around the one minute mark, at which point I can only assume that this worker, along with their computer, were obliterated in some sort of Tunguska event.

126 workers out of the 134 total survived for five minutes and were still conscious at the end to answer the question and submit the assignment. The seven workers who failed to submit most likely died peacefully sometime during this period. This gives a survival rate of about 94%, not bad at first blush, but the consequences of this will become clear shortly.

The entire experiment took a little over an hour, with the average time to complete the assignment being 5 minutes 52 seconds (I provided 15 minutes total for each assignment). Shockingly, all surviving workers correctly completed the humanity test at the end of the five minutes. Also, no evidence of time travel (aka $('form').removeClass('hidden')) was detected.

Amazon charged an additional 20% of what I paid to workers (Fun Fact: In the year 2036, the 29th Amendment actually makes the “Amazon User Storage” fee federally enforced—the entire United States having been found to be a giant Amazon warehouse—with 20% of all income automatically withheld for the privilege of renting space therein).

Total cost of the experiment: about eight dollars.

Side note: Besides my own amusement, I sincerely hope this experiment made workers smile and made a few people’s days slightly more awesome. Mechanical Turk can be great, but it’s dehumanizing by design. Read into this experiment what you will, but it was never about Mechanical Turk specifically.

Scaling It Up

The 94% survival rate of my initial experiment was promising, but why content ourselves with saving a handful of lives and leave the masses to their fate? Let’s scale things up. Why not use Mechanical Turk to keep all 7.4 billion humans alive? Let’s fund the survival of everyone!

Although I’m still seeking financing to put this plan into action, the numbers show that funding humanity’s survival using Mechanical Turk would actually be far cheaper, and far more effective (at least depending on criteria), than one may imagine.

Universal Survival Funding

There are 288 five minute spans in a day, so, at the old five cents per five minute rate, keeping a single human alive would cost $14.4 dollars per day. Far too extravagant! Now, since it would probably be bad taste to pay some people less than others to stay alive, let’s just pay less across the board. That’s progress!

Mechanical Turk sets a minimum payment of $0.01 per assignment, which gives a much more reasonable rate of 2.88 dollars per human per day. Using the adjusted numbers, it will cost about $1050 dollars to keep a human alive for a year. This is about the nominal, per capita GDP of Zimbabwe.

We’ve also found a fun new unit to measure expenditure. The one hundred million dollar price tag of an F-35 fighter is just so mundane and uninteresting with those units, so why not divide by a thousand to express the cost of a new F-35 as one hundred thousand years of human existence. Of course, we can further divide existence into lifespans which, assuming a generous average lifespan of eighty years, gives the F-35 a true cost of 1250 human lives. Much better!

Under this plan, it will cost us 8 trillion dollars to fund all humans for a year. Amazon will then take an additional 1.6 trillion dollars each year (BTW buy AMZN), for a total cost of around 10 trillion dollars per year.

Much moneys, but if you consider that the global world product is closer to 80 trillion dollars per year, it’s actually fairly reasonable.

And the World Will Go On Just the Same

Say we onboard all 7.4 billion humans to Mechanical Turk and are all ready to start funding their survival. The species should be all set, right? Not so fast. We’ve overlooked a crucial factor: just how dangerous it is to work for Mechanical Turk.

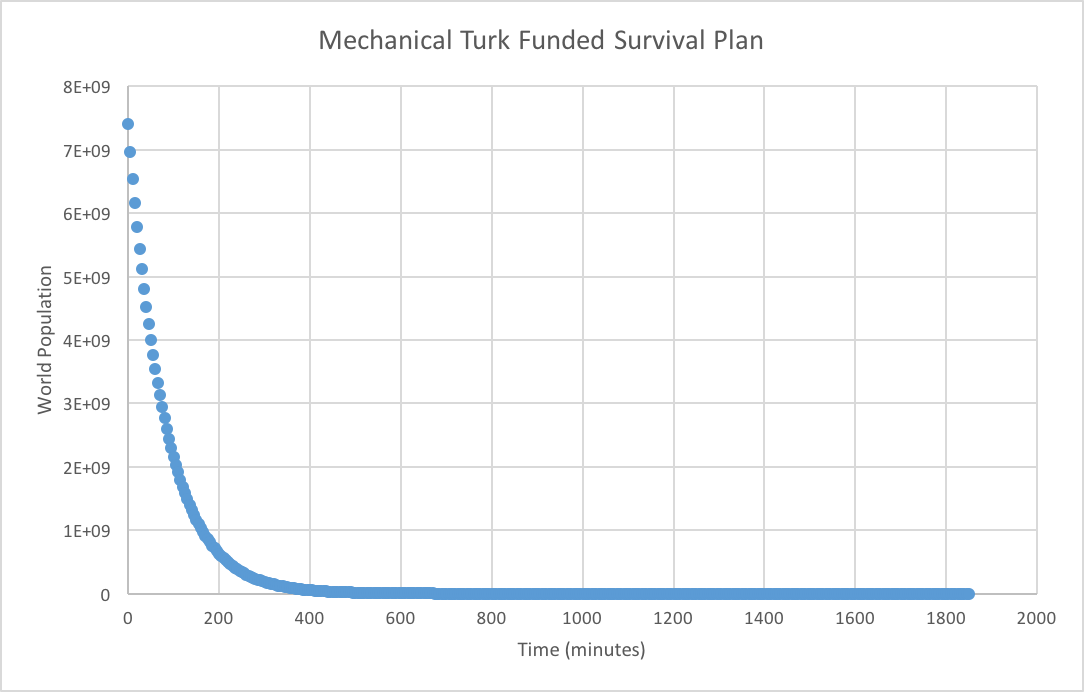

Ignoring all variance due to age, illness, and living conditions, a human has about a 0.789% chance of dying each year, which works out to a 0.0000075% chance of death in a given five minute timespan (a fun fact for every occasion!) However, my experiment shows that a Mechanical Turk worker has a 5.97% chance of dying in a given five minute period, making Mechanical Turk employment around 800,000 times more dangerous than normal existence.

Around 440,000,000 people are going to die in the first five minutes once we start funding their survival. There’s nothing we can do about that, it’s just how the numbers work out. In fact, more people will die in that first five minute span than have died in all major, modern human conflicts combined.

One hour after instituting Universal Survival Funding, the world population has been cut in half.

After an entire day (288 assignments) only a few hundred survivors remain, scattered across the globe. Alone in silent cities, they pray to the timer—their new god—for one more iteration.

The last human will start their last assignment midway through the second day.

On the plus side, we don’t have to pay the dead, reducing expenses considerably. Rather than ten trillion dollars, the total cost of the plan will be around 8 billion dollars, practically pocket change in the scheme of things.

And just think! We’ve eliminated poverty, war, and disease. Not bad for two day’s work. Not bad at all.

I’ll take my Nobel posthumously.