The Quest for the World's Ugliest Photo

And we’re off! Sun at our back, wind in our hair, and Minolta’s finest 21mm lens in hand.

Before us: the new 520 floating bridge, a ribbon of concrete stretching two kilometers across Lake Washington and bringing two shores together—man’s final triumph over Poseidon, or something like that.

We’ve waited and waited, and now the grand opening is finally upon us, a day of celebration atop this modern leviathan. A day for us to enjoy the sheerer majesty of this creation—the sheer majesty of all creation in fact—before this aquatic paradise is forever sullied by utility.

But the future is the future. Today we are alive! Today we are out on the new bridge, camera in hand, with 20,000 of our fellow creatures. And today, the quest to capture the world’s ugliest photo continues!

Of The Lens

King Arthur had Excalibur; Sir Gawain his Galatine; our weapon of choice for this post-modern Grail Quest: a NEX-7 sporting a Minolta MC W. Rokkor 21mm lens. A nice enough camera, sure—albeit a tad APS-Cy for us moderns—but what a lens! What a lovely lens!

Minolta has outdone themselves once again with this 1973 vintage. It’s not the smallest or sharpest lens for the money, or even really much of a good lens optically, but this is a case where the whole is much greater than the sum of its parts. Distortion, flare, chromatic abrasion, and general optical finickiness; all on full display with this baby. It’s imperfect to say the least. But, then again, so are we.

And yet, as of things and their idiomatic coverings, this is a lens that only reveals it’s true grace after prolonged intimacy. Call it romance, call it Stockholm Syndrome if you will, but there’s something to be said about imperfect gear that just feels good to use and just produces good looking results, measurement and objectivity be damned.

So, what of the lens?

Take the lens in hand. The first thing you notice is its bulk. Ultra wide-angle lenses like this are not exactly known for their svelte physiques—and while, at about 3x3x3 inches in size, this is actually one of the smaller members of that genus—this lens just feels big. Solid, that’s the word for it. Contrasted with modern ultra wides, there are no weight saving composites or modern optical setups to be found here. No, here we have what amounts to a tube of glass encased in a full metal jacket.

That’s only a slight exaggeration. This is one of the most complex light-benders Minolta ever produced, and the lens contains both the largest number of optical groups (9) and largest number of optical elements (12) of any Minolta SLR lens. But more on the optics anon.

Minolta released two 21mm f2.8 lenses: a MC II styled MC W.Rokkor-NL and a MC-X styled MC W.Rokkor (styled Rokkor-X in North America.) Both are prime examples from Minolta’s golden decade of lenses, starting roughly with the MC-II lenses of the late 1960s and ending with the second wave of MD lenses in the late 1970s. To be sure, great lenses exist both before and after this period, but the lenses of this golden decade generally offer an excellent balance of optical quality, solid construction, nice handling, and repairability.

The two 21mm f2.8 Rokkors are almost identical internally and optically, although the later Rokkor-X has a superior coating that cuts down flare and glare considerably. But the lenses are quite different cosmetically.

Although both editions are great in their own right, the Rokkor-X has to win out, if for nothing more than cosmetics. Just look at it! Now this is a lens. This is a lens that looks good and that makes you look good just by association. The improved optics don’t hurt either.

A big reason that lenses from Minolta’s golden decade hold up so well today, is that they are almost exclusively manual. No autofocusing or circuitry or any of that modern nonsense. This will turn off some people—I must admit that I too like all that lens metadata, and modern autofocus is often more accurate than focusing manually—but manual lenses like these offer a different sort of shooting experience, one I ultimately find far more rewarding. As long as there are photographic sensors, and so long as people still record two dimensional images on them, these old Minoltas will continue to just work.

Getting past first impressions, we now begin to explore the lens’ operation. Turn the focusing ring. The movement is smooth, precise, and tactile. The lens can focus down to a spot a quarter meter away, and, at infinity focus, hold objects roughly four feet away and on the horizon in focus at the same time. This is great for landscapes. The aperture control ring is pretty standard Minolta fare, but well executed. A satisfying click delimits each stop between f2.8 and f16.

In sum, this is just a nice lens to use. It feels good in the hand, and responds exactly as expected. And while initially off-putting, in many ways, the lens’ more ample build is actually beneficial; with the extra length and girth providing a nice stable grip when framing a shot or when making adjustments.

One final caveat before returning to the field to discuss optics: this review is about using the Minolta 21mm Rokkor on an APS-C camera, giving an effective focal length of around 30mm instead of 21mm. Crop sensor cameras nicely cut out the edges and corners of the image, where the heaviest distortion and blur will be.

Let us begin.

Westbound

Gear checked and inspected, we leave the buses behind to start westbound on the new 520 bridge.

Ahh the west! Manifest destiny. Across these waters, the Emerald City glimmers in the afternoon light, but today’s Yellow Brick Road has taken on a decidedly more stormy countenance. A light breeze keeps temperatures comfortable and is kicking Lake Washington into a wonderful chop, and there’s an appropriately nautical note in the air.

When Jesus walked on water it was called a miracle, but what’s most shocking in these modern times is how pedestrian the same feat is. Here we are, an island of life adrift in a void—surrounded by consciousnesses, each a universe unto itself—and yet not a single miracle in sight! Pity. So we turn our gaze downwards. Yes, the concrete is in rare form today and we are here to capture it in all of its glory.

So we dart around extended families walking twenty abreast; through the gnarled food truck lines a hundred deep; past many a sight that catches the eye but cannot be captured through the crowds.

And suddenly, space! A full three lanes for us to work with, plus a pedestrian path alongside. Now our work can finally begin.

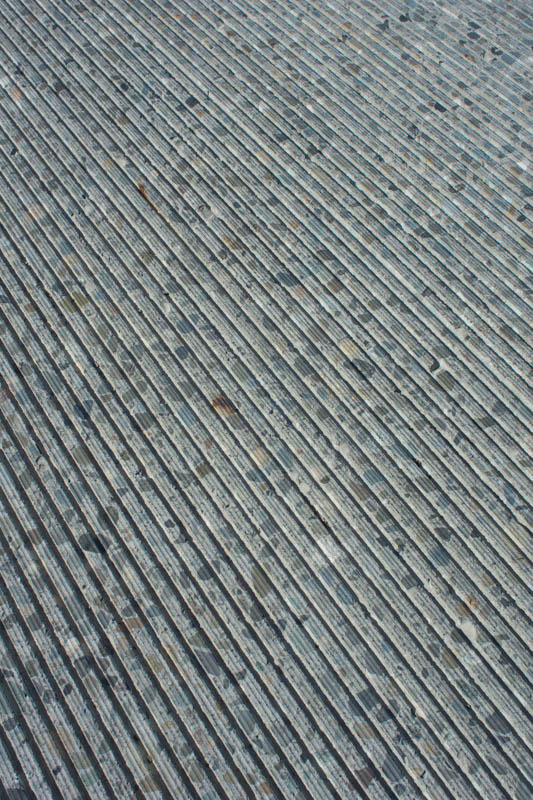

We look down. Fine grooves are etched into the road deck, creating an enormous karesansui upon which WSDOT’s artisans have unleashed a flood of creative expression.

Strewn across this well textured gray canvas are small splashes of color—spray painted crosses and circles and text—cutting social commentary by some elusive street artist no doubt.

Not to be outdone in scale, and certainly not in brashness, a Young Turk has laid down a thick yellow line across much of the span. Less a painting than a very flat sculpture, this yellow line seems to float atop the road deck, its unnerving straightness interrupted only by subtile lumps every few feet. Such a bold work could easily come off as dictatorial, but the piece shows remarkable deftness and constraint on the part of the artist.

Since its unveiling, this masterpiece has already made a big splash in the art world, and its influence on Christo’s The Floating Piers is quite obvious. But when compared to this installation on Lake Washington, Mr. Yavacheff’s effort on Lake Iseo is at best derivative and rather sophomoric.

It’s impossible to capture the majesty of these works, but you can’t blame us for making fools of ourselves trying. Claiming the leftmost lane, we stand spreadeagled, camera aimed downwards, leaning slightly forward to capture the concrete head on. When mounted to a small camera like our NEX-7, the size of the 21mm Rokkor actually provides a nice grip. And this focal length is perfect for capturing the ground without capturing one’s feat, although managing lighting and shadows in such shots can be tricky.

Click. The first photo of the day. The ice is broken.

When properly focused, the Rokkor 21mm is a sharp enough lens. Like most lenses, it is sharpest center frame at around f8, although the edges are perfectly usable as well, at least on a crop sensor camera. But this probably isn’t the best lens for your one hundred megapixel behemoths, or for billboard sized prints at 300dpi (extremely common use cases judging by many photo forums.)

We have to move quickly while shooting though, lest we create a human traffic jam or be steamrolled by the myriad phone users wholly absorbed in their little screens. Focusing quickly and extracting all of this lens’ potential requires some familiarity, as just a hairsbreadth separates a perfectly focused photo and a slightly blurry one. Much sharper and more forgiving lenses exist, both from the period and especially today, but ultimately: ‘tis not the sharpness of one’s sword that counts, but the skill of the swordsman.

Continuing on. The farther out into Lake Washington we stride, the thinner the crowds become. At the one kilometer mark, halfway across the span, the bridge even begins to feel rather empty.

This newfound openness gives us space to flit from sight to sight, kneeling down here in reverence to capture a particularly interesting gap in the road deck, there to examine a watercolor delicately splashed across a Jersey barrier. Beyond landscapes, the 21mm Rokkor is a fine lens for close up shots like these. A touch of barrel distortion is noticeable when framing straight lines or squares, even on a crop sensor, but this can be easily fixed in the Photo Shoppe if required.

More troubling perhaps, is chromatic abrasion. While not severe, and not uncommon for lenses of this vintage, CA may turn pixel peepers off this lens. At 100% magnification, this is most visible as a thin red band between high contrast areas of scenes, such as the outline of a shape against the sky.

The roadway now gently begins to rise. Unlike the old 520 floating bridge that sat atop the water—and where, on particularly gusty days, crashing waves could make one’s commute an altogether nautical experience—the new bridge deck sits twenty five feet above the water, atop seventy seven concrete pontoons. This gradual rise climbs up perhaps another twenty feet before leveling out. And although we can see that the bridge continues straight, our path now starts veering left.

We soon discover the reason for this detour. As it stands, WSDOT seems to have built a proper bridge to nowhere, one that stops well short of the Seattle shore. Out over the water to our right, the deck we had been on has split off, and now comes to an abrupt end, like an oversized olympic diving platform. Then ahead, our path on the new floating bridge makes an unceremonious detour back on to the old highway infrastructure.

There’s a longer term vision at play here.

Where the new bridge deck abruptly ends, two rows of great pillars rise from the water, like the columns of some Atlantean pantheon. These columns, and the stretch of roadway they will eventually support, are part of the almost equally ambitious West Approach Bridge North Project, connecting the Seattle shore to the new 520 floating bridge. It really says something that a two kilometer masterpiece like the one we just crossed, is only one part of a much grander vision.

Whereas the 520 bridge crosses Lake Washington’s deepest abysses atop floating concrete pontoons, the West Approach Bridge North Project stays closer to shore, in a marshy wetland. The support pillars here sink directly into the earth. It will be a while before the whole project is finally realized, but, until that time, we can hardly complain, since there’s some great construction action on display here today.

There’s another bus stop at this end of the bridge for the grand opening, and the deck is filled with poor souls, desperate to escape, stuck in hour-long lines. Rich, poor, young, old, all are equal before the busses. No coins can bribe these ferrymen.

While it is not our time to leave just yet, at least let us provide a bit of unintentional entertainment for these departers. Spotting a nice patch of concrete, we stand statue-like for moments on end, camera aimed at the ground. A little further up, we sujud ourselves before our concrete god in order to capture a particularly nice low angle shot of a Jersey barrier. This performance draws a few amused glances, but goes mostly unnoticed.

If only they could see what we see. If only.

The World’s Ugliest Photo

But say you, “Matt, my good sir, I’ve followed you this far, but must inquire: what’s with photographing concrete and roadways and other such nonsense? Surely that is not photography. Surely that is not beauty!”

To answer, allow me to slip into something a bit more singular for a moment, and wax pretentious of the world’s ugliest photo.

Some people photograph flowers; some people photograph flesh; I photograph concrete. Yes I declare there’s nothing better than a slab of concrete in the soft evening light; excepting perhaps, a nice slab of concrete in the soft evening light, with some rusty rebar atop it (although I generally don’t traffic in smut like that.) Concrete, that’s what is best in life Conan my dear fellow.

I say all this only partially in jest. After all, this is coming from a man whose Mecca is the Hanford Site; Reactor B, my Kaaba.

Concrete and industry and road signs and grime and traffic cones and utility, are just what I find interesting and beautiful, far more so than any stunning landscape or artful nude. The shapes, the colors, the textures…

You may not understand this, or worse, only understand this as hipsteresque irony or as winking artistic masturbation. But photography is my way of trying to share what I see in the world, even if some people find the results quite ugly at a glance.

So what of this “world’s ugliest photo” then? Mere clickbait my good friend, as the term is not even remotely accurate, but it is admittedly useful shorthand for the purposes of this conversation.

For one, the world’s ugliest photo is not actually ugly. It’s not a bad photo, or a poorly taken photo, or even a photo with an ugly subject matter, but a photo that ignores, or even subverts, conventional expectations of beauty and photography. The world’s ugliest photo is going to National Parks and taking photos of trashcans because they are beautiful. The world’s ugliest photo is pointing your camera at the ground when everyone else points their’s forward. The world’s ugliest photo is finding more beauty in a cracked parking lot than in the Grand Canyon. It’s something you create because you need to. And maybe other people will enjoy it or find meaning in it, but that is never the goal.

Restated: if truly taking photographs for expression, and not just documentation, never be constrained by conventions or standards. I find concrete and industry beautiful, so I photograph those. But if you really do find moraines or mammaries beautiful, great; photograph those. Just don’t create anything because that’s what everyone else is doing, or because that’s what has always been done, or because that’s what will get you the most likes on Instagram. Find what moves you and try to share it, but don’t require the world to care or even understand.

All rather grandiose and narcissistic sounding, I know. At the end of the day, I’m just that weird guy who photographs parking garages, often with mediocre results at best. But at least it’s authentic. At least it’s what I enjoy.

And that’s my world’s ugliest photo.

Eastbound

Now let us return to more solid ground. A pirouette, and we begin eastbound.

A father and daughter shoot down the hill to our left on roller-skates, carving back and forth across the concrete as they sink into the crowd. Beyond, the bridge still shimmers with life like a colorful mirage, and Evergreen Point hovers in the distance like one of Morgana’s castles. From where those people stand across the water, we too are just another indistinct blotch in the masses, just another glint in the sunlight. No camera can capture this.

Looking down at the road deck from these lofty heights, the bridge looks oddly lopsided. Only the eastbound lanes are open today, while the westbound lanes remain off limits. And, despite the old Dutch adage that half a bridge is better than no bridge at all, the temptation of the other side is difficult to resist.

Along the Jersey barrier border running down the center of the bridge, it’s not uncommon to find a dreamy youth or dewy-eyed baby boomer gazing longingly at the forbidden emptiness of the westbound lanes. Dream away my good lads, dream away. But do not act! for to dangle but a toe across this squat Berlin Wall is to receive a stern warning from the Grepo stationed along it—and, although we personally decline to investigate further, Schießbefehl is presumably in full effect.

Beyond the westbound lanes lies the old 520 bridge, floating perhaps a hundred feet to starboard. This too, closed today. It’s reward for more than half a century of dutiful service: watching this flashy young replacement spring up alongside—stealing both glory and world record, and casting the old bridge quite literally in shadow. And soon, it will be unceremoniously dismantled and forgotten. It too was once new; it too once had a grand opening. So goes life. The new may be new, but just imagine how prime the old bridge’s concrete must be after these fifty years… makes one all quivery just thinking about it.

But let us content ourselves with what we have. In the afternoon light, and looking upon things from a new angle, the eastbound lanes of the new bridge reveal an entirely new set of delights.

The road deck now bears many a sign of the day’s festivities, from multitudes of dropped french fries, to the overflowing trashcans, to the mysterious splotches of liquid that fill the concrete grooves. The atmosphere is altogether more relaxed now too, less festival than casual get-together.

With the sun no longer directly overhead, it’s worth noting that the Rokkor 21mm doesn’t do particularly well shooting parallel to the sun, humbly declining to outshine good old Helios at his own game. Direct sources of light in a scene tend to produce flare. The flare is not terrible, and sometimes even desirable, with the appealing hexagonal lens flare lending a vintage credibility to images.

Better results are found by shooting at least a quarter turn from the sun’s axis. Even here however, scenes with high contrast—say, for example, a block of lovely concrete framed against the bright afternoon sky—tend to get washed out.

One solution: polarization. The 21mm Rokkor takes 72mm filters, and Minolta also made a small lens hood for this model. A nice polarizer knocks the brightness of the heavens down a notch or two, making photographing all but the most contrasty scenes much easier. A polarizer, a lens hood, or both, are all but essential when shooting the 21mm Rokkor on a sunny spring day like this.

Many of the same attractions catch our eye as we pass by them again: that daring yellow line, the signage, the spray painted street art on the concrete. But there are new pieces on display as well.

A forest of twenty metal poles, each eight feet high, catches our eye. Next to this sculpture, a low, unconstrained fountain covers the concrete, the grooved lines of the road deck just visible beneath the reflection. Further up, two large blue containers sit overflowing with colorful tissue. Everywhere, we see echoes of people, echoes of the day gone by.

And how can we have come this far without mentioning this lens’ inner beauty? While this is undeniably a great looking lens—with optics that look nice and clear from where we stand—a great many pretty things are but facades, that, once opened up for investigation or for repair, actually prove to be quite unpleasant. Take Minolta’s MD lenses. Many are great lenses optically, but use materials and construction techniques that limit repairability. And you can forget about repairing most modern lenses yourself, what with their motors and circuitry and adhesives. Disgusting.

Open up a 21mm Rokkor for repair though, and you’re in for a treat. Again, as a product of Minolta’s golden decade, the internal construction of this lens is simpler and better than that of early Rokkors, while also being far more repairable than later MD lenses. It’s just a joy to take one of these lenses apart and see how it all works. This is an ultra wide-angle, so the design is not nearly as simple as with the normal length MC lenses, but almost every piece of this lens can be accessed, and the pieces are made of high quality materials. Again, it’s not exactly simple, but very repairable. Even the optics can be fully disassembled to access each of the 9 groups.

The day is winding down now. People still walk the bridge, but the crowds are gone. The sun is sinking lower in the sky, softening the light and lengthening the shadows. Too bad we can’t stay for sunset.

Return

And now here we are, back at the buses. Walking mostly straight, somehow we’ve ended right back where we began. The bridge is awash in contradictions like that: it’s a place now both inexpressibly familiar and unknowably indistinct, a place we only just arrived at and the only place we’ve ever known.

Our 21mm Rokkor is looking as fresh as ever. Not so with us. Batteries drained, legs aching, and mildly delusional from dehydration, this is the way it always had to end. The day began filled with promise and possibility, and now all that remains are our photos, an infinity distilled to some 200 odd images.

Was it all worth it?

Sure we captured more than our share of concrete and road deck, but the world’s ugliest photo remains as elusive as ever. Then again, was that ever really our goal? While Arthur’s knights never found the chalice they sought, perhaps they stumbled across a truer immortality through the quest itself. We still speak of them today, don’t we? Maybe the world’s ugliest photo is not a photo at all.

So what conclusion to make of the Minolta 21mm Rokkor? What are it’s strong points and flaws? How many stars does it receive?

This review doesn’t pretend to answer any of those questions. All I know: for the past four years, this is the one lens I never leave home without, and I’ve captured 95% of my photos with it. A few photos are good, many are bad, and some are quite ugly, but each one tells of a place and time that struck me in some way, and that I wanted to capture. Through this flawed lens, I’ve seen the world more clearly than I ever could with a collection of a hundred better ones.

Is this the lens for you? Perhaps, perhaps not. Or perhaps—just as the world’s ugliest photo is not really a photo, and just as this review is not really a review—perhaps the 21mm Rokkor discussed herein is not really a lens at all.

So go forth! find your concrete; find your 21mm Rokkor; and never look back.

Links