I Don't Know How We Can See Each Other Through All This Blood

A concern: how do I know that I am still alive? Without sensors and data to confirm that my heart is still beating, I could be dead this very moment without being any the wiser! Clearly, something had to be done.

So, taken with a fit of self-quantification, and building on my initial work in the modded reality space, I recently put together a device that modifies my vision using my heartbeat, thereby allowing me to monitor and confirm my continued existence. It’s pretty simple actually. The device collects data from a heartbeat sensor and uses the beats to modulate a video stream from a camera mounted in front of the eyes, sending the altered video to a VR headset.

More so than any dull numbers or graphs, this device makes you acutely aware of your body and its autonomic functioning. Perhaps too aware. Watching my heart beat was, if anything, extremely stressful, as I grew ever more convinced that each beat would surely be my last. Still, the experience suggests some neat ways to remix senses and biosignals, so allow me to detail the implementation and share my experience.

Overview

This experiment builds on the same hardware and software framework as my hands-for-eyes project, so let’s skip over the basics to look at the new and interesting bits.

The high level design was this:

- Capture realtime video using a camera mounted in front of the eyes.

- Also collect realtime heartbeat data using a sensor.

- Stream both the video and heartbeat data to webpage a loaded on a phone. The phone is mounted inside a Google Cardboard VR headset.

- Using WebGL, modulate the video stream using heartbeat events.

- Wear the headset and see what happens.

Vision

This time around, rather than getting all creative, I decided to match the tried-and-true, socket in skull vantage that most people know and love. In some ways, this view was actually far more problematic than some of the others I previously explored, as it is so familiar that emulating it can quickly fall into an uncanny valley.

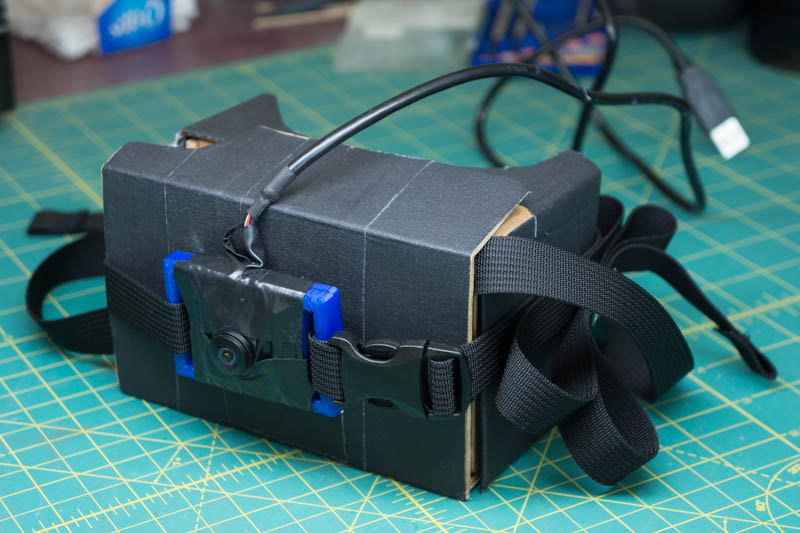

My first attempt mounted a usb fisheye camera to the front of the Cardboard unit.

This camera is connected to a Raspberry Pi. A 60fps stream of 800x600 mjpeg images is sent over LAN to a tethered iPhone. Glass to glass latency is around 100ms.

However, trying out this new headset, I quickly found that issues such as latency and resolution, that had been among the least of my concerns when viewing the world with cameras mounted to my hands, now were fairly noticeable.

Take resolution. A regular iPhone 6 delivers, at best, well under half the pixels per eye as a Vive or Oculus, and using an 800 by 600 video stream (which gets crammed into a 667 by 750 rectangle for each eye on the iPhone), the effective resolution is less than a third. This low resolution was never a major concern previously, but it did contribute to a general feeling of detachment and unreality. Here now, when looking upon the world from a more “normal” perspective, I found the low resolution was much more noticeable. Like when faced with one of those quaint old 320×240 videos on YouTube, I kept expecting a quality increase that never came.

Then there’s the latency. The need for low latency in virtual reality is fairly well documented, and many of those learnings also apply to this setup. While 100ms lag is not terrible—and is, in some ways, not as bad as a 100ms delay in truly immersive VR—there is a slight mismatch between your senses and your vision. Everything just feels a little off.

To improve latency, I also tried using the iPhone’s forward facing camera directly. This is far easier to set up and works fairly well, although you do have to slice up the Cardboard a bit to expose the phone’s camera. This pipeline also has well under a quarter of the latency.

The downsides are that the iPhone camera is mounted fairly far to the side of your head, so the view moves about oddly when you turn your head about. And, even on its widest, the iPhone lens is just not quite wide enough to provide convincing immersion. A fisheye or wide angle lens adapter would do the trick, but mounting such nonsense to a phone is just plain silly. Far better methinks to tether your iPhone a Raspberry Pi that you are wearing as a backpack, and stream video from the Pi to your phone using a usb webcam.

Heart Beat Sensor

When it comes to heart sensors, the vast majority of wearables and sensors only expose higher level data, such as heart rate. This was a little too indirect for my liking. I wanted to detect each and every heartbeat in almost realtime, and use the individual beats to modify my vision.

To accomplish this, I opted to use the aptly named Pulse Sensor. This small analog sensor measures light absorption in skin to indirectly track heart beats, and, while not terribly accurate or reliable, it works well enough.

Needs more tape

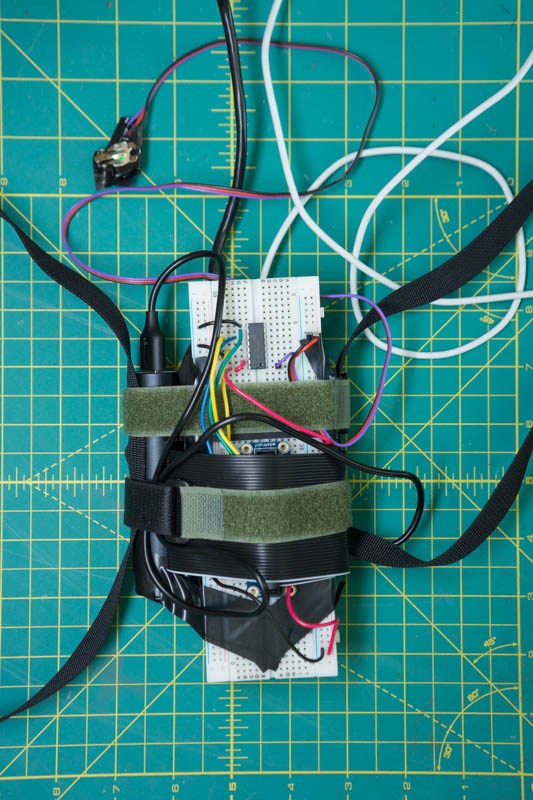

Now, as Apple cynically omitted a breadboard from recent iPhones (and wouldn’t adding a breadboard be true courage my fine fruity friends?) I also hooked the Pulse Sensor up the Raspberry Pi. The Pulse sensor is analog so its signal is feed through an mcp3008 analog to digital converter.

The entire setup is wired up on a full-sized breadboard taped to the Raspberry Pi, because why not.

Given that previous iterations of this device looked somewhat suspect and may have drawn unwanted attention if left unattended, this time around I figured that adding a veritable rainbow of colorful wires would show just how good natured this little device is.

I’m using the same Pi backpack mount described previously, but now with a breadboard fastened on too. Surprisingly, the thing held up better than I could have expected.

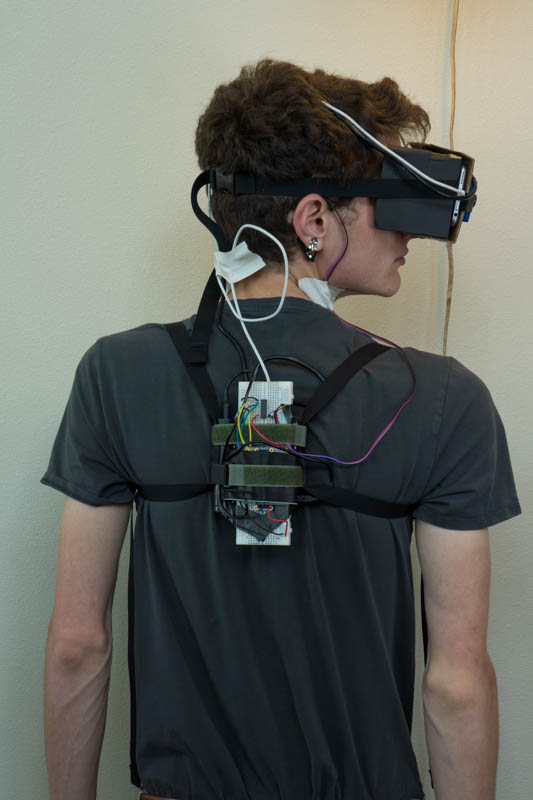

Just when you thought he couldn’t possibly look any nerdier, Matt Bierner boldly proves the doubters wrong once again. Amazing!

I attached the Pulse Sensor to my earlobe. It takes a lot of trial and error to get the sensor to work reliably, but, when properly adjusted, it did seem to match my pulse fairly well.

Software

The Pi has two jobs, streaming video from the camera and collecting heartbeat data. Streaming uses mjpeg-streamer:

mjpg_streamer -i "./input_uvc.so --device=/dev/video0 -r 800x600" -o "./mjpg-streamer-experimental/output_http.so -w ./www --port 8080 --nocommands"

This exposes an mjpeg stream at http://PI_IP:8080/?action=stream_0.

For the heartbeat data, I used a Python script to sample the Pulse sensor every two milliseconds or so. The raw data is pretty noisy, so the script applies some basic logic adapted from the Pulse Sensor Arduino example code to detect when a heartbeat actually occurs. Heartbeat events are sent to the phone over a websocket. You can find both the sensor script and website source here.

A webpage running on the iPhone collects both the mjpeg stream and the heartbeat events from the Pi.

I wanted to use an OpenGL shader on the video stream. To do this, the mjpeg image (loaded inside a normal img element) is drawn onto a canvas before each WebGL rendering, and the canvas is converted to a WebGL texture that is drawn to the screen.

The heartbeat events update uniforms on the shaders to modify the view. Each heartbeat also triggers a *ping* sound, which is altogether essential when dealing with anything medical.

And I Can See My Heartbeats

My first experiment visualized heartbeats as rushes of blood.

Beats are shown as a red vignette on the screen, which quickly fades out before the next beat, an effect not unlike which some video games use to indicate low health. (It also strikes me that it would be interesting to build a real life version of Amnesia’s “sanity” using biosignals.)

After slipping the headset on, it took the pulse sensor around ten seconds or so to stabilize and start picking up my heart beat reliably. The rate was a little under once a second, around 80bmp.

The red flashing did capture my attention for a moment, but then faded from notice while the beeping became part of the background noise. You would naturally expected that it would be very hard to see much of anything through all that red—just as you would expect that all that incessant pumping of blood and throbbing of organs would, given their vital nature, dominate one’s concerns—but, such matters quickly took a back seat as I began to explore and observe the world about me.

Walking about and interacting with the world was fairly easy and familiar, since the camera perspective at least somewhat matches normal vision. The latency however is noticeable, especially when I quickly turned my head.

Having reassured myself that my heart was beating fairly reliably, I next figured on taking the ol’ ticker through its paces with some calisthenics. So, with an obligatory declaration of “it’s go time!”, I dropped to my knees and completed a grueling slog of three pushups (a personal best).

Quick demonstration of the view and showing increasing my heartbeat with a bit of exercise. The ethernet cable was only used to capture the video. It is not normally required.

This mighty labor sent the red vignette into a strobe-like flashing. As I rested and watched the flashing slow back down and stabilize again, I felt very in tune with my body in an odd sort of way. This also started me thinking, and that’s when the real trouble began.

Now, when it comes to the subject of blood, I am prone to growing at least somewhat lightheaded, if not going full swoon like any proper Victorian lady. It’s not even the sight so much as the concept. When I contemplate veins or arteries or generally anything circulatory, my own blood rather quickly flees its loftier dwellings for lower and less introspective organs. There’s something humorously pathetic about a creature that cannot think too closely about the very processes and substances that sustain it without passing out, but so it goes. And given that just taking my pulse by hand can induce this general lightheadedness, in hindsight, this experiment was perhaps a poor choice.

Watching the red flashing, I began to imagine the blood that it represented. All that blood, and those veins, and my heart, pumping away. It all seemed rather fragile, and a bit too close for comfort.

And soon, the red flashing inexplicably began to speed up again. But instead of reassuring me that all was operating as expected, the effect was quite the opposite. The headset and backpack felt tighter and tighter. It was a classic feedback loop that, at some point, detached itself from reality and started feeding solely on itself.

For some reason, it took me a surprisingly long time to remember that I could just remove the headset and blissfully return to denying my mortality.

My Heart Beats and I Can See

But perhaps I was thinking about heartbeats all wrong. Instead of associating them with blood and mortality, as my first experiment did, consider that without a heartbeat, there’d be no vision at all. It’s the absence of a heartbeat that should really concern us, not its presence. So I decided to reverse things a bit.

For my next experiment, I updated the view so that my heartbeats illuminated the world for a flash, before everything fades back into darkness.

Putting on the updated headset, things started out a bit claustrophobic. Without a heartbeat signal, you are literally blind. It’s a huge relief when that first beat lights up the world, and an even greater relief when the sensor starts picking up beats reliably.

With a reliable signal, the visual effect is far more pronounced than the red vignette overlay. I never forgot that I was wearing the headset, but I did quickly grow more comfortable. The first half of each beat lights up the world fairly brightly, while, during the second half, the scene is too dark to see much of anything. I initially moved about in bursts during the daytime phase of each beat. I’d take a step forward or reach a hand out, before pausing during the brief night phase, and then continue where ever I left off when the next beat lit up the world again.

I soon became more confident stitching together a model of the world during the sighted period, and using this model to navigate around more fluidly. The strangest sensation is when you expect a beat, but none comes. Or perhaps there is a beat out of sync with the rest. This can really throw you off, and can even be dangerous if you really need the next beat/flash to make a decision.

Perhaps watching my heartbeat was now a bit old hat, or perhaps because this view was more obtrusive and because it used black instead of red, but I never found myself growing concerned the same way I did previously. It was just fun to watch the flashings increase and decrease as I navigated my body about the world.

Thoughts

Although this device did a great job letting me know that I was alive, I can’t help but feel that it’s best not to be constantly reminded of such things. Better perhaps to just enjoy the experience, and worry about the hows and whys later.

I am biased of course, but I also feel the device offers an interesting take on self-quantification. For me, the movement’s traditional obsession with data and optimization reeks of immortality, and most devices for the purpose are just plain boring. This device on the other hand makes you more aware of your body, in a much more direct and enlightening way. It’s one thing to read 65bpm on a screen, and quite another to see the world flash into existence each time your heart beats, and to see this happen sixty five times a minute. I certainly know which one I find more truthful, even if I don’t always like what this truth suggests.