Yield Not

Hark! Node 6 is out now and bringing the ES6 like never before. With so many great new features on tap, allow me to offer a case study in performance for just one new area: iterators and generators.

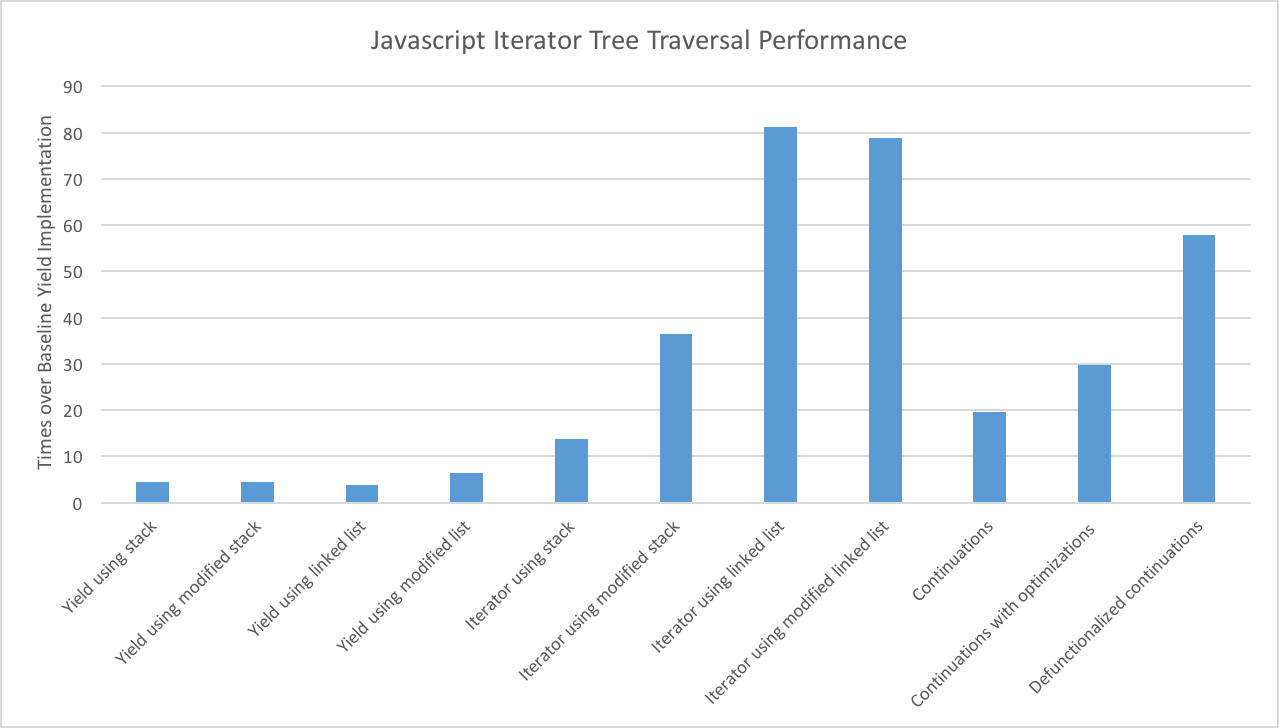

While authoring a small directed acyclic word graph (DAWG) library for Javascript recently, I needed an ES6 iterator to traverse a tree. I found that, as with most things, you can have elegance or you can have performance, but not both. There was an 80x performance difference between my initial, generator based implementation and what I was able to come up with after a few optimizations.

Now this post isn’t actually going to be about writing the fastest tree traversal iterator, but the case hopefully offers some general performance and optimization insights. Let’s take a look.

Links

The Players

Consider a generic k-ary tree:

function Node(value, children) {

this.value = value;

this.children = children; // dense array

};

const example_tree = new Node('a', [

new Node('b', []),

new Node('c', [])

]);

Our goal is to write a function that takes one of these trees and returns an iterator that performs a pre-order traversal of that tree:

const values = (root) => /* something happens */;

Array.from(values(example_tree)) === ['a', 'b', 'c']

We cannot mutate the underlying data structure and will optimize for performance as much as reasonable, without getting bogged down in micro-optimizations.

All benchmarks are taken against a perfect, 8 level ternary tree with around ten thousand nodes.

The Baseline

First up, using a generator:

function* (root) {

yield root.value;

for (let child of root.children)

yield* impl(child);

}

What elegance! What style! Truly, this must be the future!

And we can perform a full 20 traversals a second too! That’s like 199,998 more nodes per second than my organic neural circuitry could ever hope to handle.

Let’s take this as the baseline.

Stack

But we can do better. Why recurse when we can iterate? ‘Tis the imperative way.

So goodbye call stack! we hardly knew thee, let us while away (sorry) with a stack of our own devising:

function* (root) {

const stack = [root];

let head;

while (head = stack.shift()) {

const children = head.children;

if (children.length)

stack.unshift.apply(stack, children);

yield head.value;

}

}

The code grows less clear, but it’s not unreasonable yet. And this small change yields (so sorry) big performance gains, being around 4.5 times faster than the baseline.

shift and unshift are used because this is a pre-order traversal, but cast aside such draconian ordering to loll in push/pops (so, so sorry) for a solid 5x performance boost. A million nodes per second. Amazing!

Iterator

But say, do we even need a generator? While there’s much coder cred to be gained by bedecking functions in * and yielding whenever possible, perhaps there’s something to be found in more handcrafted and artisanal code that dispenses with such niceties.

So, let’s roll our own iterator using the same stack based approach as above:

function StackIterator(root) {

this.stack = [root];

};

StackIterator.prototype.next = function () {

const head = this.stack.shift();

if (!head)

return { done: true };

const children = head.children;

if (children.length)

this.stack.unshift.apply(this.stack, children);

return head;

};

StackIterator.prototype[Symbol.iterator] = function () {

return this;

};

Every time I write a stateful iterator, I die a little inside.

But such mortality is well worth the price of admission, for our hand rolled iterator is 2.5 times faster than the stack based generator, and around 12.5 times baseline. Now we’re playing with power.

Modified Stack

One more optimization.

Observe that our example 8 level perfect ternary tree has around 6500 leaf nodes and 3300 interior nodes. This means that around 9800 nodes are shifted onto and off of the stack during iteration (because we are using unshift.apply, unshift is only actually called 3300 times but it moves 9800 elements.) With a small rewrite, we can get away with only pushing internal nodes onto the stack.

function* (root) {

const stack = [{ children: [root], i: 0 }];

let head;

while (head = stack[0]) {

const node = head.children[head.i++];

if (node) {

const children = node.children;

if (children.length)

stack.unshift({ children: children, i: 0 });

yield node.value;

} else {

stack.shift();

}

}

}

A poor man’s pointer, in the form of i, is saved in the stack to track progress through child arrays. This is far more efficient than mutating or slicing arrays.

I’m not a fan of this code and the initial generator results are also not too promising; performance is about the same as the stack based generator: 4.5 times baseline.

Turn back now to our hand rolled iterator, and apply the same optimization:

function ModifiedStackIterator(root) {

this.stack = [{ children: [root], i: 0 }];

};

ModifiedStackIterator.prototype.next = function () {

var head;

while (head = this.stack[0]) {

const node = head.children[head.i++];

if (node) {

const children = node.children;

if (children.length)

this.stack.unshift({ children: children, i: 0 });

return node;

}

this.stack.shift();

}

return { done: true };

};

With this optimization, the iterator that previously contented itself to a measly 12.5 times baseline, now shoots up to a commendable 35 times baseline: a 3x performance gain.

But we can do better, and where we’re going we don’t need arrays. Onwards!

List

We only touch the first element of the stack, so why not just track that element instead of the entire stack array? Time to link us some lists.

Here’s a generator using a linked list based stack:

function* (root) {

for (let head = { node: root, rest: null }; head; head = head.rest) {

const children = head.node.children;

for (let i = 0, len = children.length, r = head; i < len; ++i) {

r = r.rest = { node: children[i], rest: r.rest };

}

yield head.node.value;

}

}

Rather dense, but the basic premise is to track the head of the linked list with head and store the next node of the list in head.rest. Every time a node with children is encountered, we yield that node’s value and replace the head of the stack with a new set of linked list nodes that point to the node’s children.

Initial results using the generator are disappointing: slower than the stack based generator and only 3.75 times baseline.

Iterator

Despair not! Perhaps the linked list is a retiring fellow who only reveals its true grace among more classy company.

Here’s the same logic, rewriten as an iterator:

function LinkedListIterator(root) {

this.head = { node: root, rest: null };

};

LinkedListIterator.prototype.next = function () {

const head = this.head;

if (!head)

return { done: true };

const children = head.node.children;

for (let i = 0, len = children.length, r = head; i < len; ++i) {

r = r.rest = { node: children[i], rest: r.rest };

}

this.head = this.head.rest;

return head.node;

};

By Object’s prototype! 2x the best stack based implementation and 80 times baseline; sixteen million nodes per second!

Sure the code is a little more involved but it’s not unmanageable and, if you are authoring a library, the trade off is well worth it.

Modified Linked List

Now, having seen the performance boost offered by the modified stack over the regular stack, we apply a similar optimization to the linked list, expecting big results. Here’s what that looks like:

function* (root) {

let head = { children: [root], i: 0, rest: null }

while (head) {

const child = head.children[head.i++];

if (child) {

const children = child.children;

if (children.length) {

head = { children: children, i: 0, rest: head };

}

yield child.value;

} else {

head = head.rest

}

}

}

The generator result show promise at 1.7 times the regular linked list based generator. Does the same hold for the iterator?

function ModifiedListIterator(root) {

this.head = {children: [root], i: 0, rest: null};

};

ModifiedListIterator.prototype.next = function () {

while (this.head) {

const child = this.head.children[this.head.i++];

if (child) {

const children = child.children;

if (children.length) {

this.head = { children: children, i: 0, rest: this.head };

}

return child;

}

this.head = this.head.rest;

}

return { done: true };

};

Alas! We find the same, or even slightly worse, performance over the regular linked list iterator.

The linked list iterator at 80 time baseline was the best I was able to achieve, although you can boost things a few more points through aggressive micro optimizations, plus even more points if you perform the traversal in any order.

Continuations

A quick diversion. So much with all this stateful nonsense. Let’s look at writing a stateless iterator, suitable for more functional-style programming.

(An aside to this aside: What is a generator? In many respects, function* and friend yield are but one use case of delimited continuations. Why not add delimited continuations to your language and leave the yielding to the standard library? Delimited continuations == Rodney Dangerfield.)

Plain old continuation passing style will do us just fine:

const visitChildren = (children, i, k) => {

const child = children[i];

if (!child)

return k && k();

return visit(child, () => visitChildren(children, i + 1, k));

};

const visit = (node, k = null) => {

if (!node)

return k && k();

return {

value: node.value,

rest: () => visitChildren(node.children, 0, k)

};

};

Because the iterator returned here is stateless, it cannot be used directly in for of loops or with any of the other ES6 goodness. It’s easy enough to write a simple adapter, but here’s the loop we’ll be using to emulate for of:

for (let it = visit(tree); it; it = it.rest())

console.log(it.value);

On the plus side, we can branch, save, and pass around such iterators however we want, without worrying about the consequences. Such is the freedom of native statelessness.

This initial continuation base traversal is about 20 times faster than baseline. This puts it far ahead of all generator based solutions covered, and between the regular stack based iterator and the modified stack based iterator in terms of performance.

Optimization

We can apply a similar, leaf node optimization that worked so well for the modified stack to the continuation based code. Here we check if any children exist before actually calling visitChildren, drastically cutting the number of function calls:

const noop = () => 0;

const visitChildren = (child, children, i, k) => {

const next = children[i];

return visit(child,

next

?() => visitChildren(next, children, i + 1, k)

:k);

};

const visit = (node, k = noop) => {

const children = node.children;

const child = children[0];

return {

value: node.value,

rest: child

?() => visitChildren(child, children, 1, k)

:k

};

};

This pushes us up to 27 times baseline, about 1.5 times the regular continuation code. Getting closer, but the 80x high-water mark is still a ways off.

Crazy Optimization

We grow desperate. We must rise above the stateful filth! Time to bring out the big guns: defunctionalization.

Defunctionalization is exactly what it sounds like: turning higher order-functions (the continuations in this case) into data. Instead of passing functions as continuations, we pass continuation objects that are applied by an apply function. (I once wrote a riveting piece about defunctionalization and tail calls in Javascript and I’m fairly certain that at least ten people have read the first paragraph.)

const apply = (k) =>

k && visitChildren(k.child, k.children, k.i, k.k);

const visitChildren = (child, children, i, k) => {

const next = children[i];

return visit(child,

next

?{child: next, children, i: i + 1, k}

:k);

};

const visit = (node, k = null) => {

const children = node.children;

const child = children[0];

return {

value: node.value,

rest: child ? {child, children, i: 1, k} : k

};

};

for (let it = visit(tree); it; it = apply(it.rest))

console.log(it.value);

What we sacrifice in clarity we make up for in speed. The defunctionalized continuations implementation is about 2 times faster than its optimized continuation counterpart, and 50 times baseline.

A fun side effect of defunctionalization is that, so long as all state is serializable, you can serialize the continuations too. The technique does not scale well and is rather obscure however, and I find is only suitable for optimizing inner-loop type code. Not quite fast enough to overcome the linked list based iterator, but a good technique to keep handy if more functional-style Javascript is your thing.

Conclusion

Javascript is not C++. Abstractions have overhead and cost. It’s always important to know these performance tradeoffs and know when it is appropriate to optimize. All the implementations offered here are pretty much the same algorithmically but, with just a few changes, we went from 200,000 nodes per second to 16 million nodes per second. Not bad.

And the moral of the story is not that func-stars are evil or that to yield is sin. No, always consider application. The original generator based traversal is the cleanest and most maintainable of the lot, but it’s also by far the slowest. And that’s just fine for most cases.

If you’ve got any other ideas for iterator based tree traversal you’d like to see benchmarked, feel free to submit a PR.